Joel Drucker: Celebrating a Tennis Lover and Mother’s Resilience

F. Scott Fitzgerald once stated, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function,” in an article titled “The Crack Up.”

This was the situation for my tennis-obsessed mother, Erna Drucker, one day in 2010. Knowing the importance of a team moving to the middle of the court, she was playing doubles. She was eighty-one years old as well, and she knew that the advice for the elderly is to not fall.

Now, though, flesh overruled mind as she collided with her partner in the middle of the court. Mom went to the floor. After suffering an instant bruise, she hobbled back to her feet, drove home, visited her physician, and read a biography on actress Barbara Stanwyck to pass the time until she could return to tennis in two months. My mother, like Monica Seles was famously described by Boris Becker, was a difficult cookie.

On January 28, 2024, Erna Drucker passed away. She had been slipping into dementia for a few years, and she was ninety-four years old. Thankfully, everything finished really quickly and painlessly.

Possibly due to her birth just five months before to the 1929 Great Depression, my mother had always embodied the value of tenacity. Actually, the reason she had come to the tennis courts in the first place was her desperate need for it. Mother was diagnosed with breast cancer in the fall of 1970, when she was forty-one years old.

At the time, not much was understood about the best ways to treat this illness. The patient was instructed to cross her fingers and hope for the best after undergoing treatment for five years. We relocated from St. Louis to Los Angeles not long after the diagnosis and operation. Mom’s new physician suggested that increasing her physical activity might help her heal.

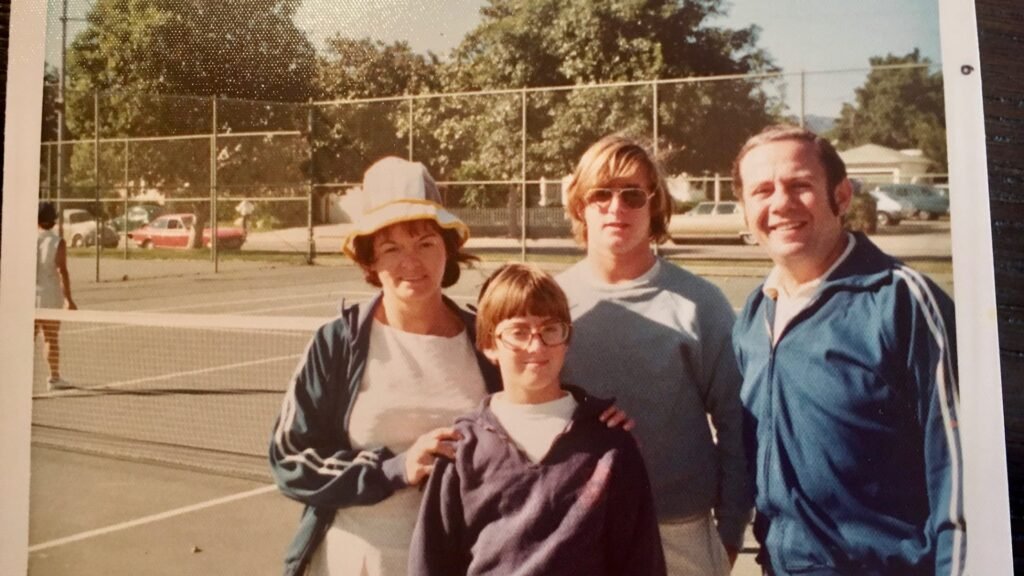

Now that she was settled in a city with constant sunshine, she thought it would be a good idea to take up tennis. Mom headed down to group lessons in Stoner Park, the closest public facility. She quickly started playing every day. Before long, my older brother Ken, father Alan, and I all started playing together. Mom got me a red-and-white Spalding Pancho Gonzales Autograph racquet for my eleventh birthday.

She quickly started to watch the professional league as well. These were the early 1970s tennis boom years, when TV coverage really took off. When my mother took up racquetball in 1971, there had been seven events that aired on American television. That number rose to 70 by 1976, around the time she and my dad joined a small club.

Many years later, mom was enthralled with Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, watching Tennis Channel almost nonstop. More recently, when I informed her that Tennis Channel’s main office was situated slightly over a mile away from Stoner Park, she was quite happy.

The fact that tennis has long been popular in Los Angeles made our family’s journey much more enjoyable. Far into the 1970s, immediately following the US Open, the Los Angeles Tennis Club played host to the Pacific Southwest Championships, which at the time was regarded as the nation’s second-most significant competition. In September 1972, Mom and a friend embarked on a 12-mile trek to the east of our West Los Angeles house.

She enthralled us with stories of seeing the old Pancho Gonzalez, the intelligent Tracy Austin, and, at the time, mom’s favorite, the royal Arthur Ashe, that evening at dinner. She remarked, “He had this silver racquet that looked like a rug-beater.” That was the insanely fantastic Head Competition frame that my parents had purchased for Hannukah the following year.

Also Read: Tennis Updates 2024: Unlocking Jannik Sinner’s Tennis Brilliance; A Comprehensive Analysis

Mom and I took a drive to The Broadway, a department store in the nearby Century City mall, a few years later, right before the “Southwest.” By now Ashe had secured his Wimbledon breakthrough victory. Mom purchased me a poster of him with the words “King Arthur” for my bedroom wall as a way to celebrate.

A makeshift court had been placed in front of The Broadway, so mom made sure I got in line to hit a few balls with Ashe. After shanking the first forehand, I made reasonable contact with a backhand. “Not bad,” said Ashe. Mom was happy to see that, and off we went back home.

But don’t for a moment believe that my mother wanted to force me to play tennis competitively. She would drop me off at a private court in Bel Air every Monday at 3:30 for an hour-long instruction with Sean Harrington, the instructor, for about a year when I was fourteen. Sean would then take me home in his car after teaching another session till 5:30. Perfect, Mom commented. “While you wait for Sean, you can read.”

Because although tennis racquets made good presents, books, ideas, stories, and authors held far greater significance in my home. My mother had given me The Glory & The Dream, a fast-paced narrative history of America spanning the years 1932–1975, at the same time I started working with Sean. Every Monday, while Sean taught that last lesson, I hiked out of the New Deal and into the New Frontier.

About her tennis, Mom remarked, “Oh, we don’t call them matches.” “We refer to them as games. It’s merely a game—a pleasant and healthy way to pass the time.

This attitude made understandable, considering the health card she’d been dealt. The good news was that everything was clear five years after the cancer diagnosis, and mom was playing tennis four days a week.

However, one morning mom’s tennis match was cancelled. One spring day in 1977, as I was leaving our apartment building, I was startled to see my mother returning home with a blouse, a pair of slacks, and other goods in her hands. Ken, my older brother, owned these. At the age of 20, he had experienced his first episode of schizophrenia eight months earlier. Even though he eventually got better, what would occur next?

Ken was probably high on LSD on this most recent occasion when he was flipping out in a Westwood hotel room with a few others. They had contacted Erna at five in the morning, requesting her assistance. When she got there, he was shivering beneath the sheets, naked. He abruptly leaped out of bed, opened the door, and ran into the streets of Los Angeles while his mother tried to reason with her oldest child.

Mother didn’t know where Ken was when I saw her that morning. Luckily, a few hours later, about five miles from the hotel, Ken would be spotted sprinting through Santa Monica by an off-duty police officer. Ken was shortly admitted to what was known as a sanitarium. Ken would spend the next 42 years of his life in mental health facilities within three years of this incident.

Here, as with the breast cancer, mom represented Fitzgerald’s idea. She went above and above with my father, Alan, to make sure Ken was safe and well. But it wouldn’t be enough to beat them. Mom kept loving tennis, primarily as a participant, often as a spectator, and sometimes as both. She and her father developed a yearly routine of traveling 120 miles east on a Friday to see the men’s quarterfinal matches at the Indian Wells ATP-WTA event, starting in the 1980s and continuing into the 1990s.

It was also convenient that the LA Tennis Club event had moved to the UCLA campus, which was two miles from our house, by the 1980s. Of course, my parents relished being there as well, especially the occasions when my press pass allowed us to park more conveniently. It was only fitting that mom would choose to have the memorial celebration for dad at their tennis club, as he passed away in 1992 at the age of sixty-six from an unexpected heart attack.

Knowing how passionate my mother was about tennis, several friends asked me how excellent of a player she was after her death. I will not tell you lies and say that she had gold balls on her mantel. Rather, I would quote an old WTA coach who told me that she “used the sport as a way to recover from cancer.” loved her time playing basketball. played all the way into her eighties. I think that’s a really good player. That’s a pretty excellent rule of thumb for any of us.

Apart from her love of books and tennis, my mother had a lifetime interest in movies, perhaps watching one every week from her early years until she was in her 90s. Billy Wilder, a storyteller distinguished for a trait mom really valued: biting wit as a doorway into the human condition, was one of her favorite directors. After my father and brother passed away, she remarked, “If you don’t laugh, you cry.”

Mom was especially fond of Wilder’s 1960 picture The Apartment, which featured a scene where Jack Lemmon used a tennis racket to strain spaghetti. Mom must have loved the moment. She also relished the last sequence of the movie. C.C. “Bud” Baxter, played by Lemmon, is playing gin rummy with Shirley MacLaine’s sharp-tongued Fran Kubelik.

Baxter says, “Miss Kubelik, I love you.” Miss Kubelik, did you hear what I said? I adore you so much.

She answered, “Shut up and deal.”

And that is what Erna Drucker did for ninety-four years, both on and off the court, from the death of her husband to the loss of a child to her own health issues.

Mom, happy Mother’s Day. I love you.